As I have mentioned before, the British Library is a constant source of cultural surprises and delights.

As I have mentioned before, the British Library is a constant source of cultural surprises and delights.

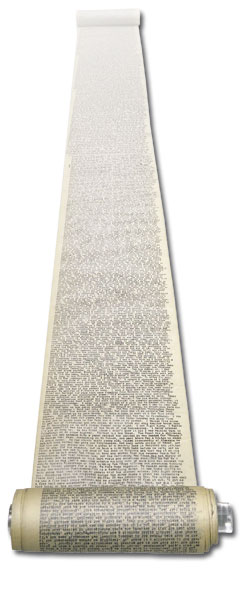

This time the source is our display of the original 150 foot long manually typed manuscript scroll of Jack Kerouac’s modern classic On the Road. I popped down one lunchtime to have a look at this unusual form of a first draft of the novel, which I had last seen in Russell Brand’s infamous BBC documentary following some of Kerouac’s routes across America.

The notes alongside the display in the library were intriguing and made it sound as though this unedited version would make for a more interesting read than the modified published edition of the book.

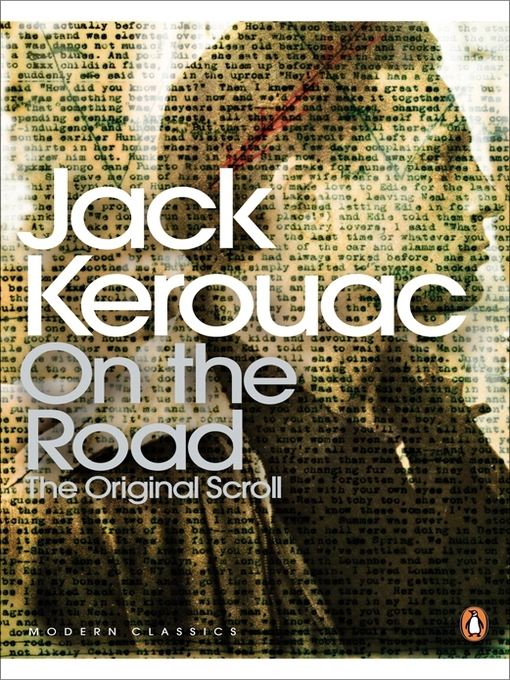

Fortunately our shop stocked both the ‘proper’ version and a Penguin edition of the original scroll (in book form). A week later and I have finished this amazingly freewheeling and raucous book and regret not having read it years ago. Kerouac is superb at bringing to life the prodigious American landscape as he criss-crossed the country hitch-hiking and driving various borrowed cars.

His evocative road trip text took me back to my gap year trip, travelling 13,000 miles around the USA and Canada on a motorbike. In particular the steamy heat of New Orleans, the vast open plains and die straight roads of Texas, and the chilly winding passes of the Rocky Mountains heading into New Mexico. I also fell in love with the poetic names of towns encountered along the way such as Indio, Blythe, Salome, Flagstaff, Wichita, Rapid City, Des Moines, Mobile, Clint and my favourite Cimarron at the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

I have to admit the idea of reading a book with no paragraphs and little punctuation was somewhat intimidating, but the story grips you like a roller-coaster from the beginning, and I found myself not wanting to get off. I enjoyed the fact this version contained all the real names, places and sometimes shocking details (mostly changed in the edited version to avoid libel cases and the censor).

As the back page blurb puts it;

‘In this influential odyssey of jazz and drugs, of filling stations and marriage licences, of sex, and poolsharks, and hiballs, Kerouac tells the real story of his travels with car thief and Beat icon Neal Cassady, and the famous friends they met, drank with, and ignored.’

Perhaps the biggest surprise came from the reading the 100 pages of notes that came with the Penguin version. The manuscript had gained mythological status from the story that Kerouac wrote it in one continuous three week blitz, fuelled by coffee and Benzedrine. I found it hard to believe such a literary feat could be produced just like that out of thin air, and the reality proved very different. The manuscript was actually the culmination of many years of experimenting and frustration for Kerouac in trying to create what he called the “Official Log of the Hip Generation”. So although written in a whirlwind of manic typing, Kerouac had several previous manuscripts to call on, as well as being surrounded by piles of notebooks and letters.

An unexpected surprise came in the last few pages of the book as Kerouac, Frank Jeffries and Neal Cassidy (the unlikely hero of the story) and roll into Mexico City towards the end of their final road trip. Apparently a dog called Potchky had eaten the final section of the scroll. It seem hard to believe that this mythological ‘dog ate my homework’ excuse used by teenagers across the world, had actually befallen the sole copy of the novel. Fortunately the editor of the Penguin edition was able to use a revised version written by Kerouac shortly afterwards, so no harm seems to have been done to the ending of story.

For me the biggest irony of the intense three week writing period designed to capture the essence of this new era, was that it took a further six years and much wrangling between the author and publishers before the print version finally appeared in bookshops.